The big and small historical details the show nails.

A side-by-side look at images from the war and the series.

It’s no surprise the long awaited series Masters of the Air has skyrocketed to the top of the charts – with more viewers in its opening weekend than any Apple TV+ series (in its first season) to date.

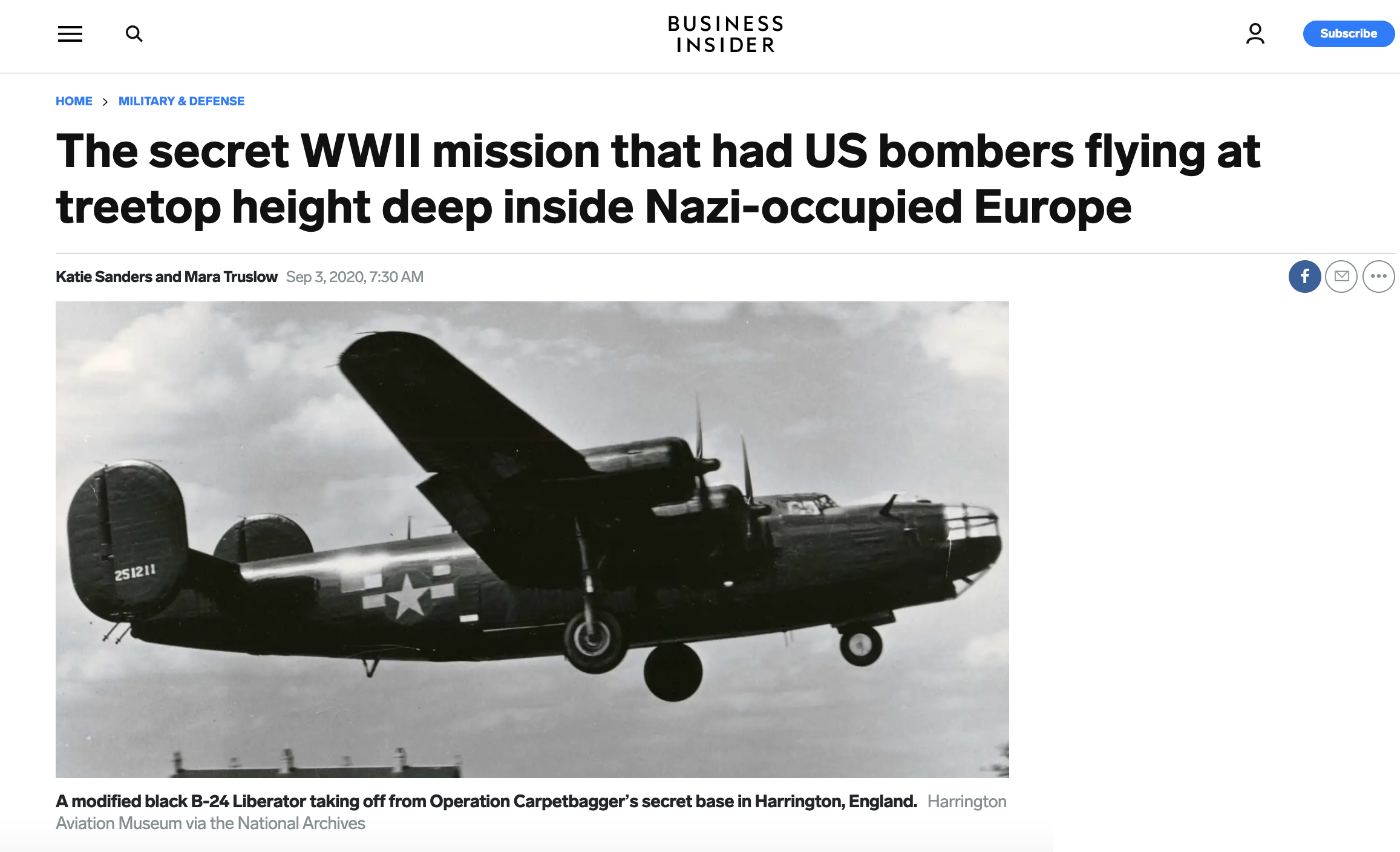

It masterfully – and accurately – tells the story of the Bloody 100th, one of forty heavy bomber groups of the 8th Air Force during WWII. They were pioneers of the air war, fighting Hitler from the skies above Europe and dropping bombs on strategic targets almost two years before Allied troops landed on the beaches of Normandy.

The show portrays a true story. Behind the scenes, production was laser focused on getting the historical details – big and small – exactly right.

So, how did Masters of the Air do in mastering the history? Impeccably well, if you ask me.

This blog series will go episode by episode, comparing stills from the show to wartime images – so you can decide for yourself.

Top – Egan and Cleven stand in front of the B-17 ‘Our Baby.’ (Photo by Apple TV+).

Bottom – A wartime image from the heavy bomber base at Shipdham of an airman mission ready.

Let’s get into Episode 1, where we meet the protagonists Egan and Cleven, airmen assigned to the 8th Air Force who are en route to war. Their destination is England, where their first harrowing missions begin.

In this episode, we’re introduced to the heavy bomber base at Thorpe Abbotts, the place they’ll call home during the war. We meet their machine of war – the B-17 bomber, with its claustrophobic, primitive interior, and the combat gear they must don to fly at altitude where temperatures hover at negative 50 degrees.

Getting Around Base – Jeeps

On screen, we see Egan pick Cleven up in a Jeep after landing at Thorpe Abbotts. Having access to a vehicle to get around a sprawling 8th Air Force base was a luxury reserved for the top brass of a bomb group – including the likes of Egan.

Everyone else on base walked, and they walked miles everyday. Getting between the airfield, the living site, and the mess hall alone required multiple miles of walking, often through mud and rain. Cleven has yet to face England’s dismal weather.

As the episode progresses, Jeeps buzz around the airfield, transporting men and material in the frenzied activity before a mission, dropping airmen off in the far corners of the airfield, where their bombers were parked on hardstands circling the runway.

Urgent news traveled by Jeep, too. A ground crewman at another 8th AF heavy bomber base recalled the tense moments waiting for the bombers to return: “The many stories of stragglers being jumped by enemy aircraft continued to send chills up my spine. And hope was almost gone. Too upset to leave the line, I kept busy moving things around, making sure everything was in readiness for her return; kicking the weeds, watching the sky, and then the Jeeps and power wagons as they busily traveled the perimeter, returning the crews for debriefing. Then suddenly, one of the Jeeps turned in and screeched ‘They’re safe!’ They landed on the coast with just an engine out. I almost needed a parachute to bring me safely back to earth.”

Getting Around Base – 2.5 Ton Trucks

Episode 1 brings the Bloody 100th to England. Crosby arrives at Thorpe Abbotts after mistaking the French coast for England – and running into flak. Bubbles greets Crosby from the back of the truck, which has been sent to the hardstands surrounding the runway – where the bombers park.

Airmen rode in the bed behind the cab, seated on two wooden benches. A canvas canopy sometimes was strung above. It was designed for eight men – but more were often squeezed on board.

2.5 ton trucks were needed to transport crews between their living sites and the airfield in the pre-dawn hours before a mission. Miles could separate the two because 8th AF bases were designed as dispersed sites to make it harder for Luftwaffe attacks to destroy the entire base.

2.5 ton trucks did more than transport men to and from war. Airmen happily hopped aboard in pursuit of fun. Liberty Runs took airmen from their rural airbases in East Anglian villages to larger surrounding towns like Norwich – where pubs, restaurants, dancing clubs – and women – offered a reprieve from war. They got three hours of freedom – from 7 to 10 PM – when pubs closed and the airmen were collected.

Riding in a 2.5 ton truck was not comfortable. An 8th AF veteran recalled, “We bounced around on those hard wooden seats in the back end. On he way back to the base we often were eating fish and chips, wrapped in newspapers, and it was a hot delicious delight.”

‘Sweating out a Mission’ on the Runway

On screen, we see Cleven’s first mission begin. B-17s file into line on the perimeter track around the runway, taking off at 30-second intervals. The signal caravan on the runway flashes its light (the black and white checkered trailer), signaling the pilot on deck to push the throttle. This sequence is historically spot on – artfully capturing the complex choreography of a mission.

As Cleven and Biddick speed down the runway, a bevy of ground crewmen stand on a jeep, waving and cheering the crew on to their target. Even though they’re just beside the concrete runway, they’re nestled in the tall grass of this former farmland, against a backdrop of blue skies. It’s an idyllic scene, a place where the machines of war are out of place.

This scene is a carbon copy of how missions began at 8th AF bases across East Anglia – at least during the few short months when England’s skies were as sunny and clear as we see in this episode. More often than not, the scene beside the runway was a cold, damp, muddy mess – as seen in the real wartime image below.

At the end of a mission, when bombers were expected to land, ground crews once again lined up beside the runway, anxiously awaiting the group’s return. Ambulances and medical staff waited there too, ready to rush toward ailing bombers and injured men before their props even stopped turning, just like we saw in episode 1.

It came to be known as sweating out a mission. They waited anxiously, peering skyward, squinting to spot the bomber stream on return. Then, the counting began, hoping to count all the ships that left at dawn.

On Cleven’s first mission, three crews didn’t return.

The Cockpit & the Captain

Episode 1 introduces us to the vehicle of the strategic bombing campaign. The B-17 Heavy Bomber is a character in its own right says writer John Orloff.

And the cockpit is its nerve center, from which the Captain orchestrates the intricate 10-man dance of a heavy bomber mission, all the while manning the controls of an incredibly complex machine.

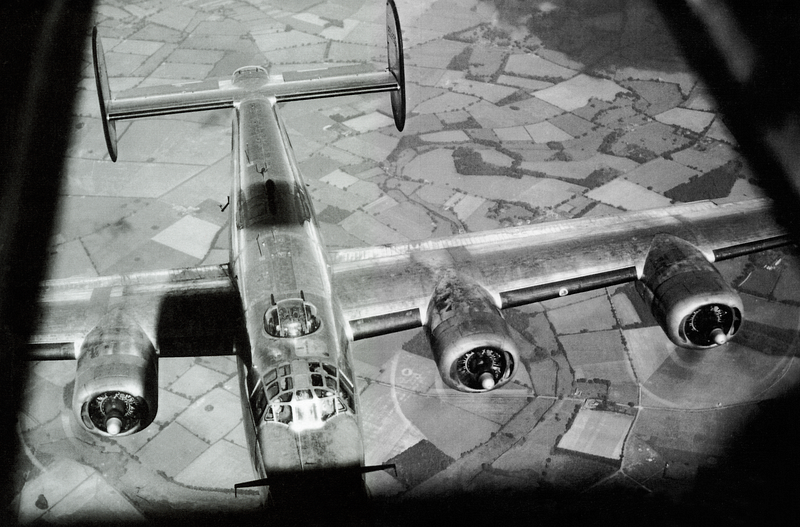

As Cleven takes off for Bremen, we get an up close look at the cockpit – and the instrument panel teeming with gauges and switches. It’s undisputed the series nailed reproducing the B-17’s cockpit, and that was no small task. The B-17’s sister ship (the B-24) had 81 cockpit gauges and controls, a 57-item checklist for takeoff, and a 27-item checklist for landing.

The cost to produce one heavy bomber in wartime was $120,000 – or $2.2 million dollars today. Challenging to operate and expensive to replace, the B-17 required a steely, competent leader in the cockpit. Over Bremen, we see Cleven reckon with the horrors of the air war for the first time – flak, fighters, and bombers in flames. He grapples with fear, frustration, shock, and sadness – but never loses his cool or composure.

As the air war began in earnest, 8th AF top brass struggled how to evaluate a pilot’s ability in combat, where survival hinged, “not the mechanics of reading gauges and flipping switches, but the manipulation of flight controls and power settings for optimal efficiency and safety of the airplane. The even more difficult aspect of piloting to measure was judgment. How will would a pilot decide whether to land or to go around whether to bail out or attempt a dangerous landing? How easily would he panic?” (Mahoney, Reluctant Witness)

Cleven did not panic. But he lands in a state of shock – tracing his hand over the holes flak pierced in his bomber. Why didn’t you tell me what it was like, he asks Egan back on base. Here, we see the roots of combat fatigue (the AAF’s wartime vernacular for PTSD) planted in Cleven.

The Flying Clothes

Egan’s first mission comes at the top of Episode 1. On the hardstand before it begins, airmen are swollen from all the gear they’re wearing.

At altitude, temperatures hovered around -50 degrees Fahrenheit – the same temperature as the South Pole. Flying clothes were all that protected airmen from the deathly bitter cold.

Drying Rooms were specially heated buildings on base where airmen got dressed. “Getting dressed for altitude flying is quite a job,” said 8th AF veterans Gerald Gross during the war.

“First came our electrical flying suit, an extra pair of wool socks, heated shoes, summer flying suit, leather flying shoes, a 45 pistol slung gangster fashion around the chest, Mae west life jacket, parachute harness, silk gloves, electric gloves, flying helmet, goggles, and lastly an oxygen mask strapped to the side of the helmet.”

All told, it was 80 pounds of gear.

(Check out the Episode 2 Recap here.)

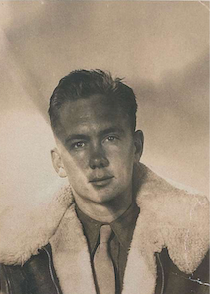

What do I know? I’m the granddaughter of an 8th Air Force veteran who flew 42 missions from Shipdham on a B-24 Liberator (the arguably better bomber – but we’ll leave that for another day). Over the last six years, I uncovered my grandfather’s war that he took to the grave – then sought to make it easier for others like me to find long lost stories from the war – by building a data dashboard and digital archive for my grandfather’s group. I’ve also written extensively about the 8th Air Force during WWII, for publications like NatGeo and Insider.

The radio program explores the story behind

The radio program explores the story behind